Ni animal ni tampoco ángel. Anatomía de la imagen: Marina Vargas

Marina Vargas has made use of the vast options offered by contemporary visual language and its disciplines to narrate, in an acute, radical, incisive, and profound way, what words sometimes fail to convey. Trauma resides in the body because it came from the body, and there were silences, but also screams. In her work, one hears a poetic body, but also a political one, in images that are truth, sincerity, in a tempered and paradoxically abysmal manner that I have rarely encountered. She draws on references from the history of art, fundamentally on representations of canonical bodies inherited from Classical Antiquity (seven heads, seven and a half, eight, eight and a half, nine… a great dilemma), but also on analogies and resources that often come from the unconscious and from letting the mind fly without limits, from chance… or from moving through life without restraint, sometimes abruptly, at other times in torrents.

In these pieces dwell affects, tactility, fragmented memories…, and she allows herself to speak in leaps; linearity is superfluous because the artist accepts confusion and error as modes of knowledge, as a formula of almost magnetic creation that infuses guidelines and energy to continue winding around what happened and what it left us: fear, fragility, strength… the friends who accompanied us in moments of panic. Addressing trauma does not seek to close it, but the simple act of generating an image about what has been lived is a form of repair and also of resistance that makes evident to what extent illness and the formulas with which it is protocolized also have gender.

The first works by Marina Vargas recovered by this exhibition at ADN Galeria greet us from behind and reflected in a large mirror. These are the sculptures that made up the corpus of the project Ni animal ni tampoco ángel and that made evident the construction of gender by demanding both a symbolic and a political reading of women’s bodies. By appropriating and manipulating statues from European Classical Antiquity that have served for centuries to establish the canon and stereotypes of beauty, and that represented certain archetypes whose origins sink into very remote times, she made evident how women (and in this the nineteenth century was especially bloody) were tied to very limited symbolic options: they could be objects of desire, sacrificed angels of the home, and, as in Puccini’s operas, symbols of redemption from sin which, for women, was the hypostasis of lust and “un-controlled” love).

In these works, which ooze a pink material somewhere between magmatic matter and cotton candy, the artist places herself in a new position that questions the Manichean readings of the two spheres: it makes evident that the construct “gender” is pure violence, relationships designed around power or submission, an inherited framework that is of no use. Marina Vargas rejects these categories and proposes another space; in reality, a limbo in which there is no possibility of conciliation, a realm in which the reading of the image cannot be anything other than political and is so, moreover, because it resists classification.

Vargas appropriates monuments precisely because they are born with a vocation for permanence and representation. And for that reason she generates new ones, showing what is hidden, what is made invisible: an “incomplete” female body does not exist for the canon (let us recall on the Fourth Plinth of Trafalgar Square Alison Lapper Pregnant (2005), by Marc Quinn, a white marble sculpture that referred to Greco-Roman statuary by portraying this British artist, born without arms and with shortened legs, pregnant and nude). Monuments construct a symbolic hierarchy in which men usually have names and are examples of behavior or heroes, while female bodies are always allegorical (let us recall in Spain Influencia cultural, y nada más que cultural, de la mujer en las artes arquitectónicas, visuales y otras by Paz Muro: with the collaboration of Pablo Pérez-Mínguez she photographed female statues in Madrid in 1975, underlining that they are never real historical subjects). And women could only be read, I insist, as the pure instinctive and exultant nature of surrealism, the “sweet” submission that generated the construct of the “ángel del hogar,” or the unreachable spiritual ideal of the weightless and ethereal woman in the nineteenth century. And Vargas is categorical: women are not a construct, but different subjects, citizens each born in a specific context, embodied subjects.

There is in these pieces prior to illness something visionary: what is that magmatic and ambiguous material that comes out of the sculptures or invades them, that grows before the impossible resistance of marble turned into symbol, yet inanimate? We have a long tradition of visionaries in the history of culture: from the Sibyls who brushed the future with an enigma without managing to narrate it or go into detail, to Hildegard von Bingen with her prophetic contemplations sheltered within mysticism. Women, in general, as illustrated by the myth of Cassandra, were discredited, silenced, if not pointed out as witches to be seen burning tied to a wooden stake. More recent examples lead me to the chewing gum that Hannah Wilke stuck to her body as decorations, but also as stigmas in S.O.S.– Starification Object Series (1974–82), only to be shortly afterward diagnosed with lymphoma and leukemia; between 1989 and 1993, Wilke documented her illness in the series Intra-Venus. Moving away from the illness of the body to enter that of souls, the novel El cuento de la criada by Margaret Atwood is a dystopia, a warning, that seems closer than we ever imagined.

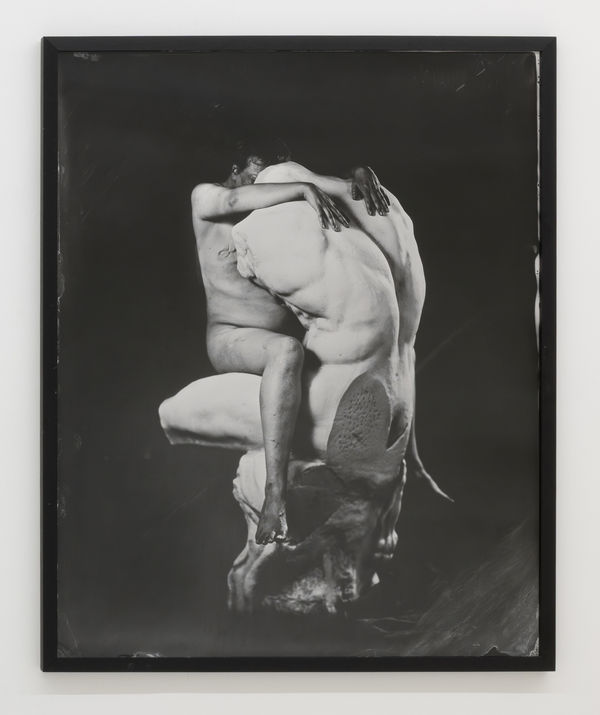

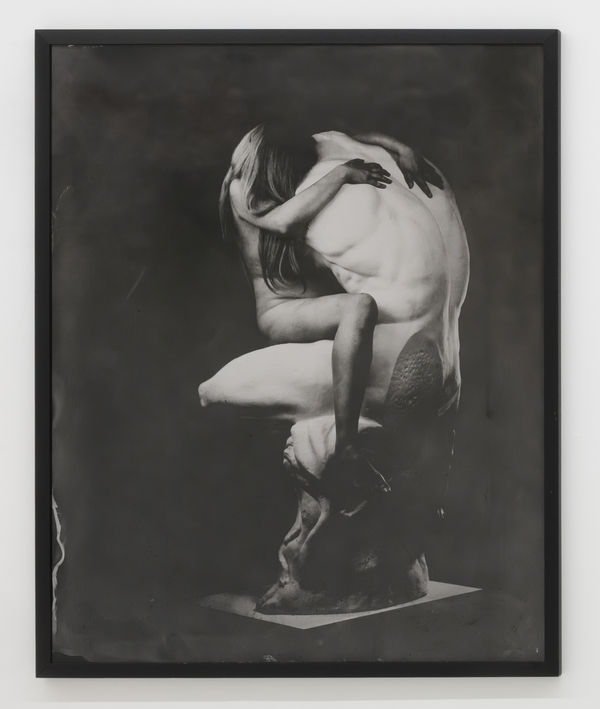

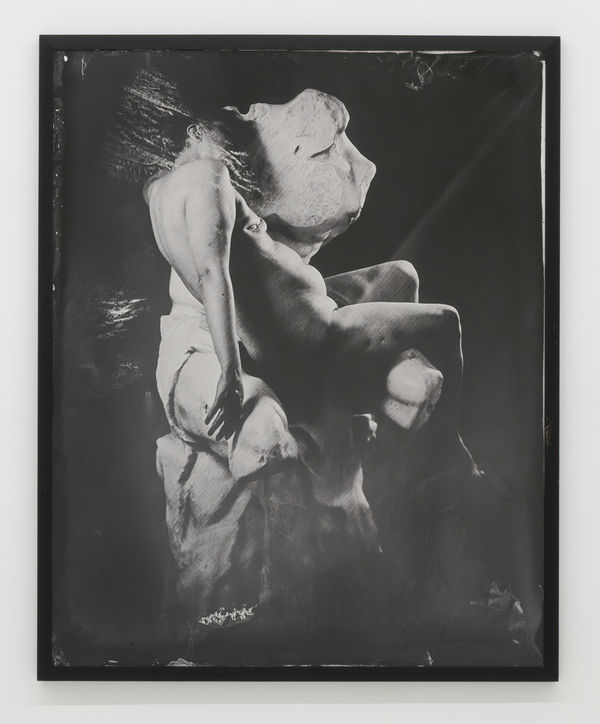

In the photographs on metal and black glass using the wet collodion process, the female body—the artist’s own after surgery, chemotherapy treatments, radiotherapy, and hormone therapy with Tamoxifeno—is presented as a symbolic battlefield. It is a body that, at times emulating the eroticized pose of a Venus, reclines alongside the erect Victoria de Samotracia, from whose wing one emerges from Vargas’s back (Has she fallen like Ícaro? Has she kept the wing as a symbol of her victory over pain and the context of illness?). It is a naked body that unsettles, that cannot be objectified: it is not smooth, it is not cold, it has pubic hair and scars, the head has lost the long and silky hair of the “nymph,” of the ethereal being. It is a body that has weight and does not offer itself to the gaze, but expels it, unsettles it. It is a rebellious, resistant, real, carnal, visceral, bruised body, a body that rises to its feet and, raising its fist, signals its strength as a form of resistance. A situated body, individualized in pain and lack, pregnant with memory and time, that climbs onto the sculpture of the most beautiful torso ever carved, that of the Belvedere from the Vatican collections: sometimes it shelters her as in a Pietà (the artist’s body embodied in the image of Christ), at other times it seems to couple in a copulation.

There is nothing more thunderous than the silence of these photographs.

Isabel Tejeda Martín

-

Marina Vargas, Venus de Cánovas o Venus Limbus, 2015

Marina Vargas, Venus de Cánovas o Venus Limbus, 2015 -

Marina Vargas, Eros Centocelle o Spiritus vitae, 2015

Marina Vargas, Eros Centocelle o Spiritus vitae, 2015 -

Marina Vargas, Ganimedes (Satélite), 2015

Marina Vargas, Ganimedes (Satélite), 2015 -

Marina Vargas, Diadúmeno (materia prima), 2015

Marina Vargas, Diadúmeno (materia prima), 2015 -

Marina Vargas, Contra el canon, 2021

Marina Vargas, Contra el canon, 2021 -

Marina Vargas, Melusina Vacante, 2015

Marina Vargas, Melusina Vacante, 2015 -

Marina Vargas, Venus Esquilina ó Carne de Adán, 2015

Marina Vargas, Venus Esquilina ó Carne de Adán, 2015 -

Marina Vargas, Yo la Llevo. Juegos y Cargas, 2017

Marina Vargas, Yo la Llevo. Juegos y Cargas, 2017 -

Marina Vargas, El abrazo, piedad y el modelo y la artista y Torso de Belvedere, 2015-2021

Marina Vargas, El abrazo, piedad y el modelo y la artista y Torso de Belvedere, 2015-2021 -

Marina Vargas, Color-Dolor, 2026

Marina Vargas, Color-Dolor, 2026 -

Marina Vargas, Ni animal ni tampoco ángel #1, 2026

Marina Vargas, Ni animal ni tampoco ángel #1, 2026 -

Marina Vargas, Ni animal ni tampoco ángel #10, 2026

Marina Vargas, Ni animal ni tampoco ángel #10, 2026 -

Marina Vargas, Ni animal ni tampoco ángel #2, 2026

Marina Vargas, Ni animal ni tampoco ángel #2, 2026 -

Marina Vargas, Ni animal ni tampoco ángel #3, 2026

Marina Vargas, Ni animal ni tampoco ángel #3, 2026 -

Marina Vargas, Ni animal ni tampoco ángel #4, 2026

Marina Vargas, Ni animal ni tampoco ángel #4, 2026 -

Marina Vargas, Ni animal ni tampoco ángel #5, 2026

Marina Vargas, Ni animal ni tampoco ángel #5, 2026 -

Marina Vargas, Ni animal ni tampoco ángel #6, 2026

Marina Vargas, Ni animal ni tampoco ángel #6, 2026 -

Marina Vargas, Ni animal ni tampoco ángel #7, 2026

Marina Vargas, Ni animal ni tampoco ángel #7, 2026 -

Marina Vargas, Ni animal ni tampoco ángel #8, 2026

Marina Vargas, Ni animal ni tampoco ángel #8, 2026 -

Marina Vargas, Ni animal ni tampoco ángel #9, 2026

Marina Vargas, Ni animal ni tampoco ángel #9, 2026 -

Marina Vargas, Pink Venus, 2026

Marina Vargas, Pink Venus, 2026 -

Marina Vargas, Ni animal ni tampoco ángel, 2026

Marina Vargas, Ni animal ni tampoco ángel, 2026 -

Marina Vargas, El abrazo, 2021

Marina Vargas, El abrazo, 2021 -

Marina Vargas, El modelo y la artista, 2015

Marina Vargas, El modelo y la artista, 2015 -

Marina Vargas, La piedad, 2021

Marina Vargas, La piedad, 2021