Most of the historically important functions of the human eye are being supplanted by practices in which visual images no longer have any reference to the position of an observer in a ‘real,’ optically perceived world.[1]

In the current hypervisual ecosystem, images —produced and distributed by political, media, and commercial logics— operate as devices of perceptual domestication. They not only saturate attention, but also configure frameworks of meaning that limit our capacity to distinguish what truly matters. Such saturation is not a neutral task, but rather responds to an economy of desire and distraction characteristic of a neoliberal system that captures the gaze and directs it toward previously coded objects, inhibiting any openness to the unexpected.

Our eyes no longer belong to us. In a regime dominated by devices of capture —visual, affective, cognitive— the gaze has become a territory colonized by hegemonic structures that orient, limit, and preconfigure what we believe we see. “In becoming the target for new mechanisms of power, the body is offered up to new forms of knowledge.”[2] Foucault warned us. Individual perception is absorbed under logics that exceed the subject, transforming vision into a vector of control rather than an autonomous faculty. What by nature belonged to us —the capacity to look at the world from an interiority of our own— dissolves into a landscape saturated with images and twisted to the point of paroxysm, determining our desires and habits. Thus, the loss is not only sensory, but existential: we cease to be owners of our eyes to the same extent that we cease to be owners of ourselves.

In this context, critical art emerges as a counter-pedagogy of the gaze, capable of fracturing the visual regimes that seek to govern our perception. Faced with the sensory domestication promoted by hegemonic structures, critical art introduces interruptions and detours that reactivate the interpretive potency of the spectator. Its function is not to offer new certainties, but to produce fissures in the automatization of seeing, forcing us to confront what is hidden behind the fictitious transparency of images. By dismantling the codes that naturalize the gaze, critical art reopens a space of perceptual autonomy in which vision recovers its interrogative dimension. Thus, rather than representing the “real” world —let us wink once again at Jonathan Crary— it destabilizes it: it turns the gaze into a reflective and resistant exercise, returning to the subject a visual agency that the system had attempted to close off.

Hence the urgency of cultivating a disobedient gaze, a capacity to see against the direction imposed upon us and to sustain the friction that emerges in the face of images that unsettle (I designate as uncomfortable any image that forces one to think). In the field of critical art, discomfort does not constitute a defect, but rather a mode of knowledge that interrupts dominant narratives and reveals zones of conflict that usually remain hidden. By exposing us to images that disturb —through their rawness, their ambiguity, or their resistance to being quickly consumed— art confronts us with the limits of our own perception and, in doing so, reactivates our critical sensitivity. In this process, visual disobedience becomes an act of emancipation.

At this point, it is especially pertinent to recall the words of Hannah Arendt “And to think always means to think critically. And to think critically is always to be hostile. […] That is, there are no dangerous thoughts, for the simple reason that thinking itself is such a dangerous enterprise. I think non-thinking is even more dangerous.”[3]. In this sense, thinking —or, what is the same, looking at uncomfortable images— implies assuming a responsibility that does not fall solely on the spectator, but also —and decisively— on those who exercise curatorial labor. The art curator is not a mere organizer of objects, but a mediator of visual experiences that can activate or numb the critical capacity of the public. Their role therefore demands the courage to show what disturbs, what unsettles, or what strains dominant narratives. Exhibiting images that force us to think is not a provocative gesture but an ethical act: an invitation to confront what we would prefer to avoid and, in doing so, to reopen the transformative potential of the gaze.

That gaze which separates itself from the arms and severs the space of its submissive activity to insert into it a space of free inactivity is a good definition of dissensus — the clash of two sensory regimes.[4]

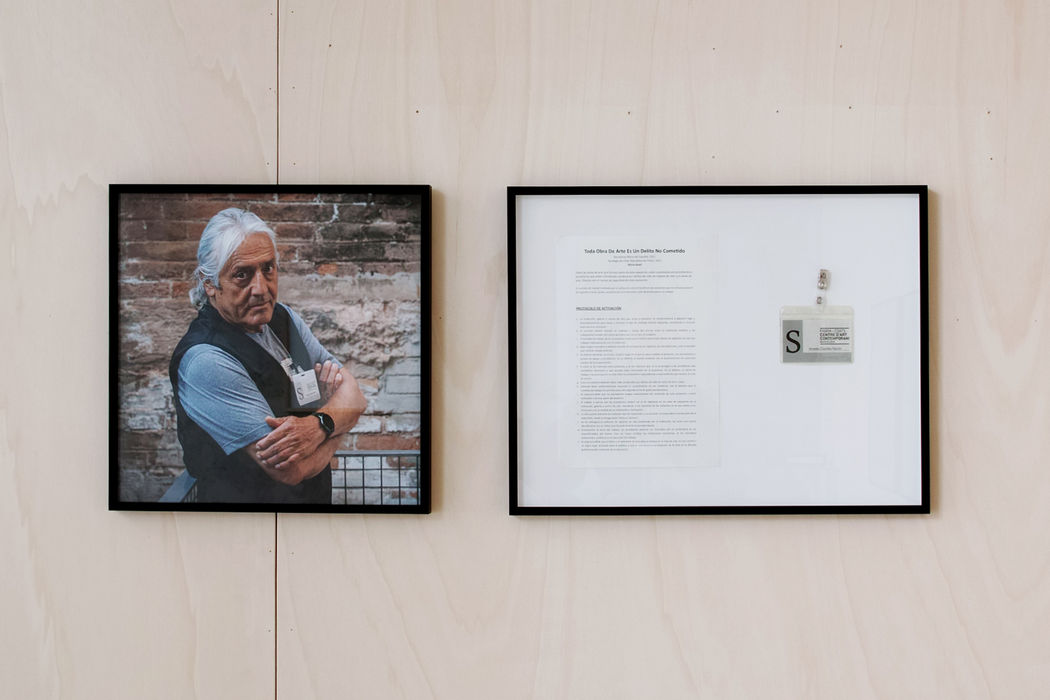

Adonay Bermúdez (Lanzarote, Spain, 1985) is an independent curator and art critic. He has curated exhibitions for MUDAS (Portugal), the National Museum of Costa Rica, Centro de Cultura Contemporánea Condeduque (Madrid), CAAM (Gran Canaria), Artpace San Antonio (USA), Centro de Arte Contemporáneo de Quito (Ecuador), Instituto Cervantes in Rome, TEA Tenerife Espacio de las Artes, the Museum of Contemporary Art and Design of Costa Rica, CCCC (Valencia), the X Biennale di Soncino (Italy), Museo Barjola (Asturias), and ExTeresa Arte Actual (Mexico), among others. He was director of the International Video Art Festival Entre Islas (2014–2017), a member of the advisory committee of Over The Real International Videoart Festival (Italy, 2016–2018), curator of Contemporary Art Month in San Antonio (USA) in 2018, curator of INJUVE 2022 (Government of Spain), and Artistic Director of the XI Lanzarote Art Biennial 2022/2023. He is a frequent lecturer at universities and museums throughout Ibero-America. He currently works as an art critic for ABC Cultural and Revista Segno.

[1] Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century (MIT Press, 1990/1992), p. 2.

[2] Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, translated by Alan Sheridan (Vintage Books/Pantheon Books, 1977), Part 3, Chapter 1, p. 155.

[3] Hannah Arendt: The Last Interview and Other Conversations (Melville House, 2013), transcript of Un Certain Regard interview with Roger Errera, October 1973

[4] Jacques Rancière, The Emancipated Spectator, translated by Gregory Elliott (Verso, 2009).