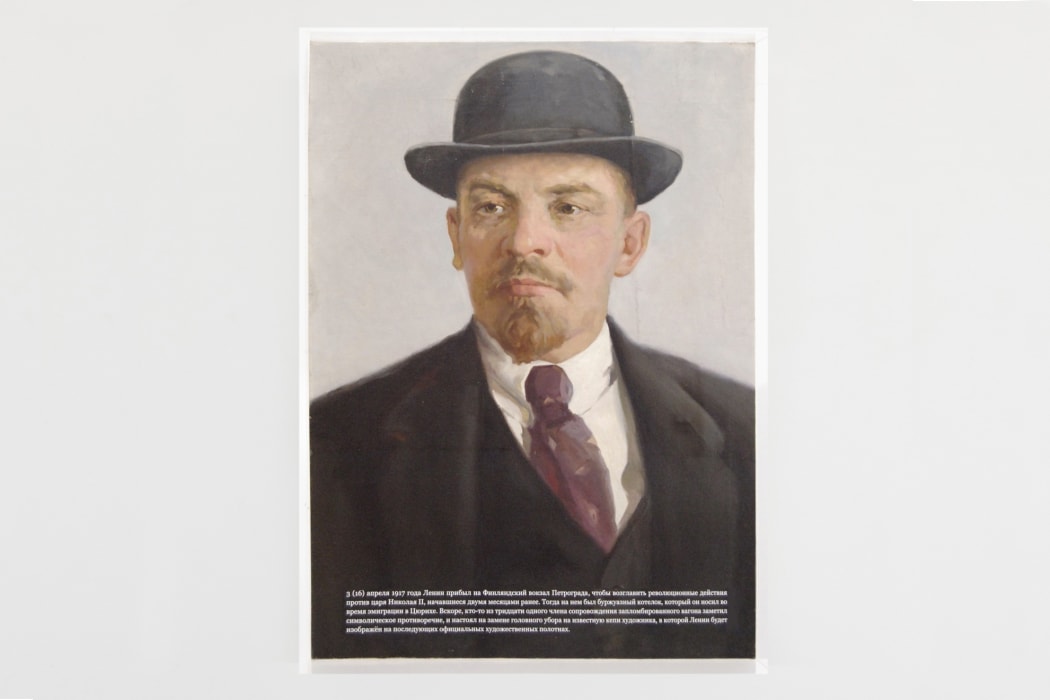

Lenin wore a bowler hat like the bourgeois he was.

In Russia in 1917 the revolts against Tsar Nicholas II were successful and the first Soviets were formed. At this point, Vladimir Ilych Ulyanov decided to return from Swiss exile to lead the Revolution and managed to organise a "sealed train", which would be able to travel the territories separating him from Petrograd without being searched or arrested. So, he arrived at the Finland Station in Petrograd safe and sound, and wearing a bowler hat, a customary item of clothing in his years of exile. Someone close to him made him realise that a bowler hat was not the most appropriate thing to harangue the proletarian masses, and from then onwards his most characteristic garment was the painter's cap he wore and with which he was to be represented in official iconography.

This iconoclastic gesture, the erasure of an identifying garment such as the bourgeois hat, replaced by the workers' cap, is the one that the artist and researcher Alán Carrasco reverses in Les faits sont têtus¹. Alán is interested in the processes of iconoclasm and collective memory, the mechanisms by which official narratives are constructed and how the elements that make them up are selected. He therefore looks at the fringes of the historical narrative and the reasons why certain aspects and actors are erased.

Lenin's hat would then be one of these elements excluded from the Soviet narrative through the exercise of iconoclasm by which they changed the garment that denoted his origins, since Lenin came from a well-to-do family and had a university degree, even though he was leading the revolution of the proletarian class to which, strictly speaking, he did not belong. I dare to speculate that, without this socio-economic background, Lenin would not have been able to lead anything beyond a couple of fights. By denying the bowler hat, class privilege is erased in order to present the leader as someone closer to the working class. The narrative of the triumphant proletariat's capability as a political force is thus manipulated. In a gesture of icon-restitution, Carrasco repaints the bowler hat onto an official portrait of Lenin and expands the narrative of this story to add layers of interpretation, which the official account had deliberately left out of the picture.

Siouxsie, Sex Pistols, Laibach, Rammstein, Glutamato Ye-yé..., the list of punk, gothic, industrial or neofolk music militants who have worn the Third Reich plate cap, the swastika and/or other Nazi, fascist or Francoist paraphernalia, among other attributes of various ideological stripes, is not a short one; in this case, direct symbols such as the aforementioned cap or the Hugo Boss military uniform, or associated or rather "assimilated" symbols such as the little "toothbrush" moustache that made Hitler so sadly famous. A style that is symbolically charged (I think one could say "infected" in this case) when it is appropriated for his figure, even though at that particular moment it was a common fashion with no other implications among the gentlemen of the time. The appropriation of the symbol here operates as metonymy, so much so that it is enough for someone to paint a moustache on a photo of Angela Merkel, for example, for the identification (and the meme) to be present. It must be said that Lenin also had a very characteristic moustache.

Although for many people it is an exercise of banalization of evil, the intention with which Siouxsie and the others used this iconography could be to annoy, to shock the bourgeoisie or to destroy the pillars of consumer society, but what is clear is that they did not fit in with what Patrycia Centeno calls "ideo-aesthetic coherence"², since their aesthetic actions did not correspond (a priori, since there are exceptions) to their ideological actions. The punks appropriated these symbols for themselves and somehow deactivated them, they changed (they tried to) their semiotic value by dissimilating them and separating them from the Nazi references. They thus ran in the opposite direction to the way, so well illustrated by Dick Hebdige³, in which dominant cultures integrate, assimilate and deactivate the subversive possibilities of the style elements of subcultures.

It is striking that in this case the dominant (and capitalist) culture, in a return journey, immediately integrates and manages by way of trade to deactivate the garments of punk style without too much trouble…, except for the Nazi symbols, of course. It is not the same thing for a punk to wear a toothbrush moustache or a Nazi headdress on stage to make a mess —along with a Ramones T-shirt—, as to be worn by girls shopping at Zara, or to be used as a costume by some Cayetanos at the Colegio Mayor or by an assailant on Capitol Hill.

Speaking of caps, the American rapper Ye (Kanye West) wears the red Trumpian cap without any embarrassment. At a fashion show he wore a T-shirt with a supremacist slogan ("White Lives Matter", appropriating and designifying the slogan "Black Lives Matter"). He also makes irrepressible racist and anti-Semitic statements. Are these provocative gestures to shock, a macho outburst, an indicator of emotional instability? Does he appropriating symbols to deactivate them or is the rapper-slash-designer really a vicious fascist and the Trumpian cap fulfills its ideo-aesthetic function on this occasion ? These gestures would unfortunately not be so striking were it not for the fact that he is of African descent, on the one hand, and has a huge media presence and influence, with many people cheering his witticisms, on the other.

All this brings me to the culture of cancellation. One of the reasons given by those who defend this line of erasure of cultural products and people with entrenched ideologies is their capacity of influence. In the case of this peculiar figure, Ye, and his symbols, it is a delicate matter because he really has a large share of attention with which he undoubtedly influences and reinforces pernicious ideologies. Even so, I have my doubts: will we in the future erase "MAGA"4 caps, or can they help us, as in the case of Alán Carrasco's work, to better situate a particular personality, to shed light on certain aspects that complete History and to tell that which is of no interest to the official narrative? It will be interesting to see how we do it in order to have a narrative that integrates these symbols in a contextualised way without banalizing evil, but without falling into iconoclasm or cancellation, with a critical eye and historical memory.

Pilar Cruz Ramón

(English translation: Beatrice Krayenbühl)

1. The facts are more stubborn than the story.

2. Centeno, Patrycia, "Espejo de Marx", ed. Península, 2013.

3. Hebdige, Dick, "Subcultura: El significado del estilo", Paidós, 2004.

4. "Make America Great Again"